REBLOGGED

http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/feb/05/mexico-oaxaca-murals-lapiztola-street-art-murals?CMP=share_btn_fb

Nine years ago, as its streets filled with flames, anger and water cannon, the walls of Oaxaca began to speak.

Stencilled commentaries – here a defiant fist clutching a pencil, there a hooded figure lobbing a Molotov cocktail or, more subversively, a book – appeared on buildings in the southern Mexican city as popular fury exploded over the state governor’s heavy-handed response to a pay-and-conditions strike by local teachers.

Their creators were Rosario Martínez and Roberto Vega, two young graphic designers who felt the time had come to move past T-shirt slogans and flyers. With Facebook walls yet to achieve their full revolutionary potential, the pair opted to use the real thing instead.

“Stencils are harder to remove,” Martínez says. “And painting a wall red says more than a little poster can – it’s like people said at the time, ‘It’s a shout painted on a wall.’”

Although Martínez and Vega’s Lapiztola collective – a pun on the Spanish words for pencil and pistol – was born on the streets of their home town, its work has spread far beyond Oaxaca and the upheavals of 2006.

In recent years, Lapiztola has used artworks to highlight everything from the cult of the drug lords and the use of genetically modified corn to the plight of Central American migrants and the enduring grief of the mothers who have waited decades to bury the bodies of their disappeared children.

Some are as dark as they are blunt: one shows bloody and terrified men in suits screaming as the many-tentacled beast of the drug trade descends on them; in El pastel (the cake), dozens of paper doilies decorated with limbless torsos and severed heads illustrate the way in which rival drug cartels have divided up the country.

“They didn’t care what belonged to whom, and that’s when the heads began to turn up and become so commonplace,” Martínez says.

After the Zetas gang began murdering people in bars as a punishment for non-payment of protection money, many locked themselves in their homes, too scared to go out.

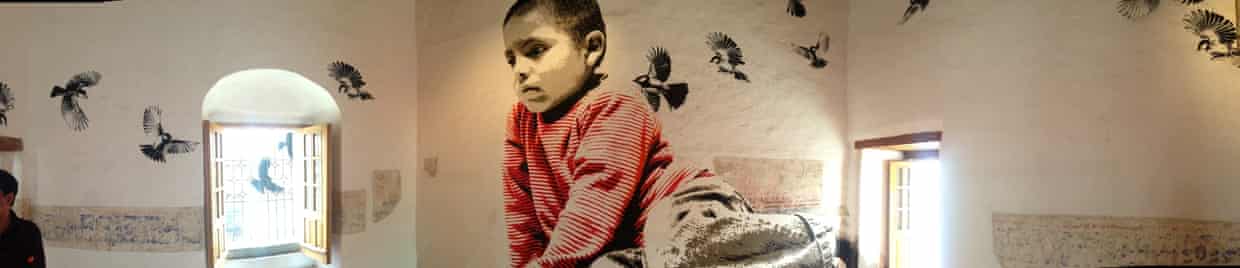

Lapiztola responded with an installation showing birds flying from a cage and heading for the freedom of the window as a forlorn boy looks on.

Similar defiance is evident in the piece that shows an angry young face surrounded by petals, and takes its title from a line by the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda: “They can pull up all the flowers but they’ll never stop the spring.”

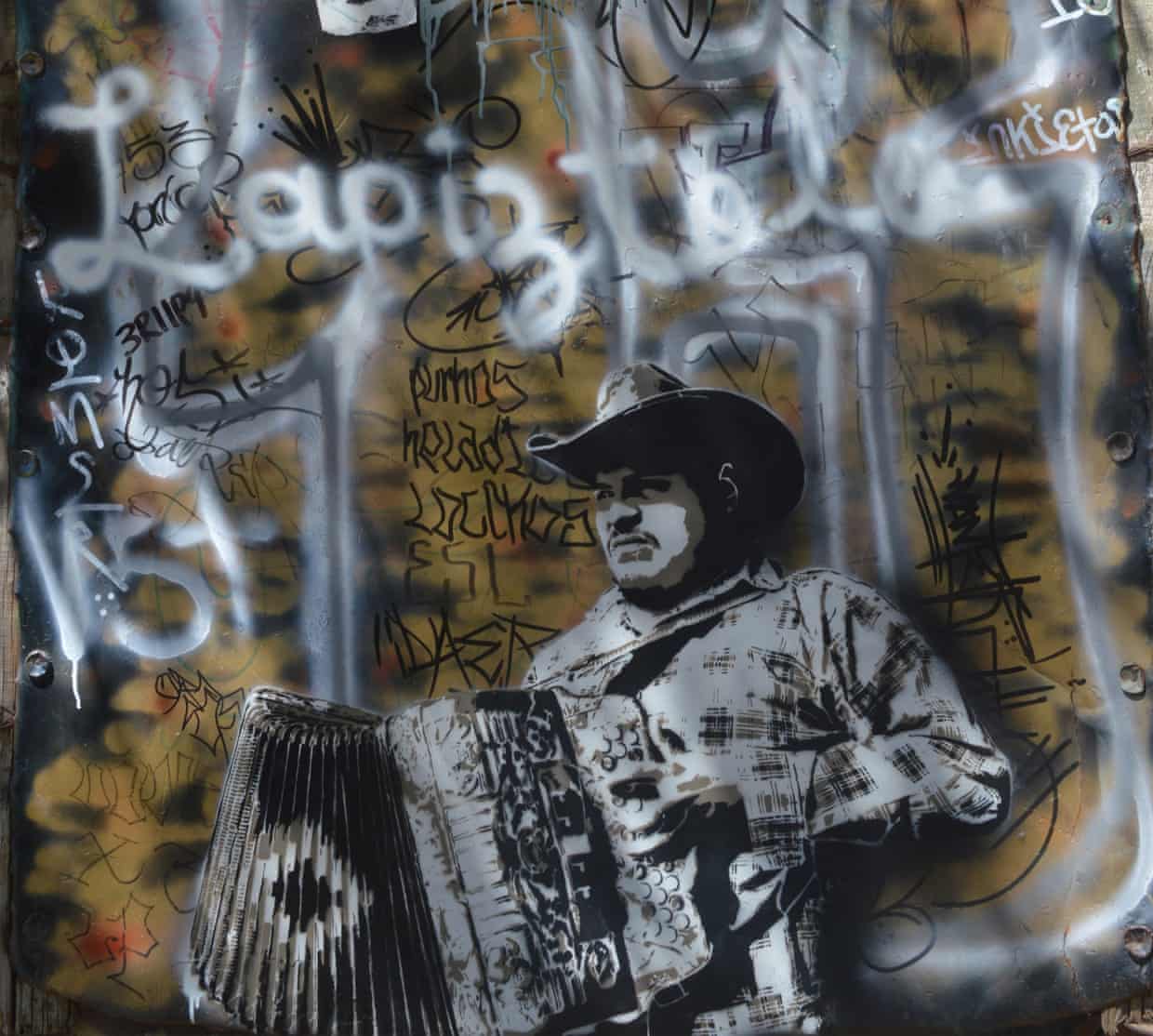

Other murals focus on the musicians who are richly rewarded for composing the narcocorridos, or drug ballads, that glorify the violent deeds of the gangs.

In one, an accordion player squeezes a tune out of his instrument while a flock of doves attacks a cartel member.

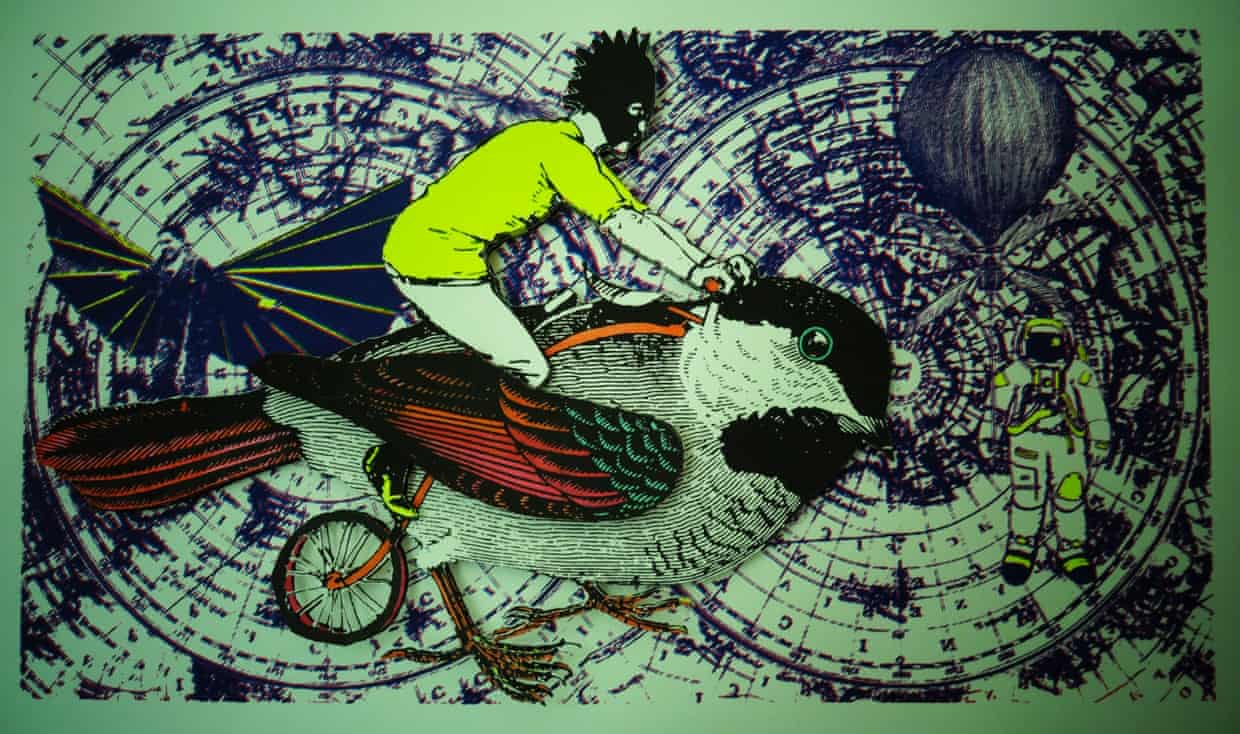

Others are more playful. Plan de vuelo (Flight plan), which chronicles the northward journey undertaken by tens of thousands of Central and South Americans, shows a figure in a lucha libre mask riding an enormous bird.

One mural, painted on the shutters of a shop in Tijuana, requires a little more explanation. It features a man with a brush scrubbing the stripes off what appears to be a zebra. However, as Vega explains, the animal is in fact a donkey painted to look like a zebra; a “zonkey”.

Once upon a time, US visitors would flock over the border to Tijuana to drink, gamble and indulge in pleasures frowned upon by the law at home.

Tijuana developed on the back of such trade and, when the visitors noticed that some of the donkeys they’d posed with for photos were too pale to show up well on film, enterprising locals obliged them by painting their animals to resemble crisply photogenic zebras.

The violence of recent years, however, has scared most of the tourists away from Tijuana.

“Now the city has no tourists, people are trying to reclaim their identities and their city, so that’s why he’s washing the stripes off the donkey,” Vega says. “He’s saying, ‘You’re a donkey and not a zebra.’”

Vega and Martínez, who are in London for the opening of an exhibition of Lapiztola’s work and to speak at a conference organised by the campaigning group Global Justice Now, hope their murals and installations will give people a better idea of today’s social and political situation in Mexico.

One mural – El abrazo ausente (The absent embrace) – has an appalling contemporary resonance.

In it, a mother still waiting for news of a son who vanished during the violence of the late 1960s and 1970s hugs a dark silhouette composed, once again, of a flock of doves.

“It was bad enough for the mothers of the students who were killed, but I think it’s worse for the mothers of those who were disappeared; their suffering is unending,” Vega says.

Four decades on, Martínez says, many mothers have been left to clutch at straws and shadows.

“They’re still waiting for news: they say, ‘He may be dead, but there’s no body so I can’t mourn him. He could still be alive.’”

The parallels with the 43 student teachers who vanished in the town of Iguala last September are inescapable, as is the growing fury in Mexico.

“When they started looking for the missing students, they found loads of mass graves,” Vega says. “Forty-three people disappeared and when they went looking for them, they found 50 other bodies, then another 10. Whose bodies are they?”

• Lapiztola’s exhibition, Democracia Real Ya!, is at Rich Mix in east London from 5-28 February

No comments:

Post a Comment